The Spirit of Aisle Two

By Sonja Hakala

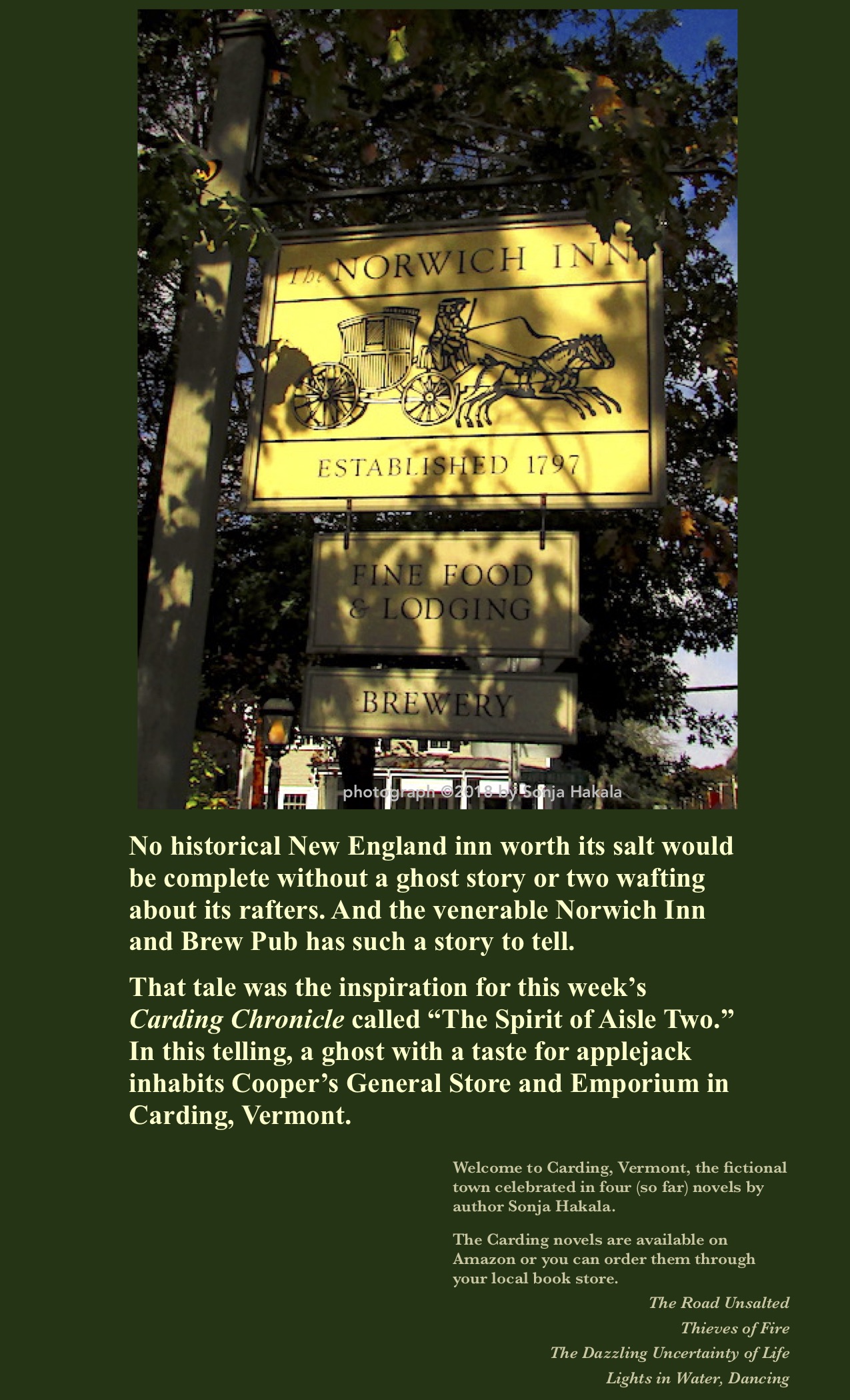

Years ago, when I was a magazine editor, I wanted a local ghost story for our fall issue. Well, in New England, ghosts (or at least stories about them) are rather plentiful.

It must be the long winters when there’s time for storytelling, eh?

Anyway, the nearby Norwich Inn had just the right story. It was about one of the inn’s former owners, a woman who appeared on the stairs or whispered around corners from time to time.

Now Norwich is just over the Connecticut River from Dartmouth College and during Prohibition, this woman hit on a money-making idea—making beer and applejack for the (then) men of Dartmouth.

I wonder if she haunts the brewery that’s still part of the Inn. (They make a great red ale, by the way.)

I loved the story and now, years later, it’s inspired this Carding Chronicle.

Carding, Vermont is a fictional town that’s at the center of my four novels. Details about them are to be found at the end of this Chronicle. Enjoy!

.jpg) If you live in Carding, Vermont, sooner or later you’ll walk through the front door of Cooper’s General store. This venerable family-owned business dominates the corner of Meetinghouse Road and Court Street on the southeast corner of the village green. It shares a parking lot with the town hall, a parking lot that’s locally renowned for its frost heaves in March, its potholes in April, and its pond-sized puddles whenever it rains too hard.

If you live in Carding, Vermont, sooner or later you’ll walk through the front door of Cooper’s General store. This venerable family-owned business dominates the corner of Meetinghouse Road and Court Street on the southeast corner of the village green. It shares a parking lot with the town hall, a parking lot that’s locally renowned for its frost heaves in March, its potholes in April, and its pond-sized puddles whenever it rains too hard.

Successive generations of the Cooper family have tried to fix these problems by alternately building up the surface of the lot, amplifying its drainage or cramming copious amounts of cold patch into its potholes. Despite all these efforts, the Coop’s parking lot always settles back into its original condition like a corpulent dowager who’s glad to let her diet lapse after the urgency of her New Year’s resolutions has passed.

The only people in town who welcomed this perpetual insistence on parking lot normalcy were the owners of the local auto repair shops—Stan’s Garage on Route 37 and Mr. T’s Auto Repair over on the Carding Turnpike. When the weather conditions are just right, these two places spend a lot of time fixing tires and rims, leading one local wag to speculate that the garage owners prayed regularly to the god of potholes.

Andy Cooper runs the family business now, the seventh Cooper to do so. His younger brother, Charlie the lawyer, lends a hand and advice when asked but otherwise steers clear of “stacking beans and carrots.” Their younger sister, Nancy, keeps the books, pays the bills, and manages the avalanche of paperwork that flows through the office. Andy’s sons, Barry and Nathan, handle the large (and growing) hardware side of the business. That leaves Andy free to tend to his favorite parts of the store—the beer and wine section, the deli, and the coffee corner. He likes to refer to these areas of the store as “the soul of the Coop” but his family knows that Andy just loves to talk more than anything so tending to these parts of the store keeps him out of their way.

Cooper family tradition dictates that the spacious living quarters above the store go to whoever takes on managing it. When Andy finally married Yvette Clavelle, they became the head household among the Coopers. The upstairs apartment was ready for them as soon as they returned from their honeymoon on the Maine coast. Sons Barry and Nathan were born there, Yvette died there, and Andy would have vacated the space long ago but there was no one ready to take his place. Nathan and his wife Tracy owned a house in the next town over from Carding and didn’t want to move. And Barry had never loved any woman as much as he loved downhill skiing in winter and boating in summer. So Andy stayed put though he found living above the store lonely without his Yvette.

It took a while but Andy eventually established a routine that kept him out most evenings. There was the Chess Club at the library on Tuesdays, dinner with Charlie and his partner Agnes on Wednesdays, supper and cribbage with Edie Wolfe on Thursdays. It all helped ease his missing-Yvette feelings a lot.

On the night of this story, a rather chilly Thursday night in late autumn, Andy walked quickly across the green from Edie’s house to the store, his normal pace accelerated by a desire to get out of the icy wind. Since the residents of Carding are renowned for their frugality when it comes to spending their local property taxes, only half of the streetlights were on, casting a pale, fluorescent glow over the evening.

As always, Andy’s eyes scanned the store’s exterior, checking for irregularities—lights left on, open doors or windows, cars in the parking lot that didn’t belong there. That’s when he spotted Evan Eakins, Carding’s night patrol officer.

“I was about to go get you,” Evan said as he lowered his car window.

Andy laid a hand on the car’s roof as he leaned in for a chat. He liked Evan, had given the boy-now-man his first job when he was in high school. “Something wrong?” he said.

“We got a call that there was a light moving around in the store,” Evan said.

“Like a flashlight?” Andy asked, glancing toward the large front windows of the Coop.

Evan shook his head. “The description was that something was glowing inside. Could be electrical.” He put the cruiser into reverse. “Let’s go look.”

Andy picked up his pace even more, pulling a large ring of keys from his pocket as he did so. Thievery was so rare at the Coop, he needed only one hand to count the incidents that had happened in his lifetime. To him, the threat of leaving a coffeemaker on and unattended was far more real than a burglary. Since the original part of the store was more than 200 years old, there was a lot of dry wood to burn.

Andy and Evan stood in the doorway for a minute before stepping inside, each of them sniffing the air like a dog on the hunt. Evan shook his head. “I don’t smell anything. Do you?”

“No.” Andy flipped on the overhead lights. “I’ll check the deli if you’ll take the coffee pots.”

Together, the two men toured the store, checking every electrical device to make sure it was unplugged and cold. Even though his employees grumbled, Andy insisted that every electrical device be unplugged at closing. “No sense taking any chances,” he’d say.

“Everything seems fine up here,” Evan said. “Shall we check the furnace?”

“Might as well,” Andy said. “I have to stock it for the night anyway.”

Andy had always been slow to make changes in the store or his life. He was one of the last people in Carding to get a cell phone, and it took his sons years to convince him that scanners at the cash registers and credit card readers were a good idea. He modernized the refrigeration system when Nancy proved he could save money on electricity, and even installed a new grill in the deli for the same reason. But he refused to convert the Coop’s heating system from its wood-burning furnace.

“I like buying my fuel locally,” he’d say. “I like keeping the loggers in business. They buy my groceries and I buy their wood. Keep it simple, I always say.”

Evan took a deep breath as they descended the stairs. His first job at the Coop had been stacking seasoned wood for the coming winter, and he still loved the scent of split logs. There was always a crew of three assigned to that task, and its repetitive nature guaranteed a lot of storytelling to pass the time. His favorite tales were of the local ghosts, of which Carding had an abundance.

Andy flicked on the hodgepodge of overhead lights, some fluorescent, some still near descendants of the ones that Thomas Edison invented. Somehow, their combined illumination never reached all the corners of the cavernous space. As the electricity zipped through the wiring to wake up the bulbs, the ones in the center began to flicker.

“Ah, there’s your intruder,” Evan started to say. “Or it would have been your intruder if these lights had been on.”

The two men looked at one another, and then Andy quietly picked up a nearby log while Evan pulled a baton from his belt. With a nod to one another, they stepped forward on little cat feet, Andy scanning the woodpile to his left while Evan did the same to the right. The shadowy knots in the stacked wood kept them tense—watchful—but they reached the opposite wall without incident and breathed sighs of relief.

“Mystery unsolved,” Evan said as they turned back the way they had come.

Then the two of them froze in place, and Andy felt the short hairs on the back of his neck prickle as an amorphous green light quivered through the basement.

“Did you see that?” he asked the younger man.

“Yeah,” Evan said. “Reminds me of the northern lights my wife and I saw when we were in Alaska. What do you suppose that was?”

Andy shook his head slowly from side to side then he said, “Something’s been moved down here.”

They probed the nooks and crannies with their flashlight beams again until they converged in the darkened center of the room. Three large barrels and a couple of bushel baskets lay in a haphazard pile. One barrel, the largest of the trio, was on its side.

“Apple Betty,” Evan breathed.

Andy’s glance was sharp. “Do you believe that old ghost story?” he asked.

“Sure. Don’t you?” Evan said. “Wasn’t she your aunt?”

“Great aunt, actually. Elizabeth Cooper. She made the best applejack in this county during Prohibition,” Andy said, and the pride in his voice was almost visible. “My father could tell some stories about her. In photographs, she looks so meek and mild but Dad said she was a wild woman for her times. Traveled all the way around the world on her own. Set up housekeeping in White River Junction with a man she never married.”

Evan laughed. “Scandalous. So why is she haunting the Coop?”

Andy’s mouth flattened. “Great Aunt Betty isn’t haunting the Coop, and I’d thank you not to spread that story,” he said. “It would be bad for business, scaring away the timid and attracting the weird. I don’t need either of those things to happen here, understood?”

“Sure, sure,” Evan said. “There’s no law against protecting a ghost, as far as I know. I’ll leave you to figure this out on two conditions.”

“And they are?”

“First, you get an electrician into this place to fix some of that.” Evan pointed his flashlight toward the ceiling where a variety of wires snaked from one place to the other. “You’ve got some very old stuff up there, Andy.”

“Umm…,” Andy began.

“No umms,” Evan said. “If this light thing we saw isn’t Betty—and you don’t seem inclined to think it is—then you’ve got an electrical problem. And no one in town would thank me if the Coop burned down because of a problem that I knew about, and didn’t push you to fix. Am I right?”

Andy sighed. “Hoisted with my own petard,” he muttered. “OK, I agree. What’s your second condition?”

Evan’s grin grew wider. “Why would Betty haunt here…,” he raised his hands to stop Andy’s protest, “instead of where she lived in White River?”

“I don’t know. Because she was living here when she died, I guess,” Andy said.

“If she was so independent, why did she move back to Carding?” Evan asked.

“For the oldest reason in the world—money.”

“So if you tell me the true story about Apple Betty, I’ll never tell anyone about the green light I just saw, OK?” Evan said.

Andy reached down to right the barrels and arrange the bushel baskets. “There’s a couple of chairs over there,” he pointed. “Drag them over and we’ll sit a minute. It’s not that long of a story.”

Once the two men settled, Andy sighed. “Cooper family legend has it that my great-grandfather—that would have been Betty’s father—was something of a religious nut, a strict Presbyterian or Methodist or Unitarian or some such.”

Evan laughed. “My wife was raised Unitarian, and they’re great liberals. It would be hard for me to believe there’s any such thing as a strict Unitarian.”

“Really?” Andy shrugged. “Well, maybe he was a Lutheran or a Baptist. I don’t know. There are so many flavors of religion, I can’t keep track.”

“What you’re saying is that the reason Betty was so wild was that her father had no sense of humor,” Evan said.

Andy laughed. “That sounds about right. Anyway, when Prohibition got started in 1920, Betty and her friend…” Andy hesitated. “Gawd, what was his name? I only heard it spoken once.” He snapped his fingers. “I think it was Dalton. ”

“Well, given the times, it’s not surprising that your family wouldn’t talk about him,” Evan said.

“Yeah, I suppose. Anyway, Betty and Dalton saw Prohibition as a business opportunity, seeing that we’re so close to the Canadian border,” Andy said.

“So they started bringing booze in from Canada,” Evan said. “I heard there was a lot of that.”

“It’s a long border,” Andy said, “so there was lots of opportunity. I gather they started doing it just for family and friends but the demand grew so they started making more trips.”

“Did someone twig to what they were doing?” Evan asked.

“Yeah. They always used to cross in Derby, and from what I heard, the guards up there looked the other way,” Andy said.

“They were probably running booze themselves,” Evan said. “Hard times. Easy money.”

“Probably. So Betty and Dalton got used to driving across with nothing more than a wave, and maybe a well-placed bribe or two,” Andy said. “My grandfather—that was Betty’s brother—told me they used to pile cases of whiskey in their back seat and even tied it to the top of their car. Then one year at town meeting in Derby, people voted in a new chief of police, and he was a rigid teetotaler.”

“And Betty and Dalton got caught,” Evan said.

“Almost. Everyone who knew her swore that Aunt Betty had this sixth sense about her. She wouldn’t necessarily know what was going to happen but she could feel things coming,” Andy said. “When I was a kid, I remember my parents both paying attention when she’d get uneasy.”

“So she knew something was wrong,” Evan said.

Andy nodded. “Once she got to thinking it over, Betty realized that none of the guards had looked directly at them when they crossed into Canada. She thought that that was what made her uneasy.”

“So what happened?”

“The American border guards were so eager and whipped up by the teetotaler police chief, they started shooting at Betty and Dalton before their car had crossed the line. Betty said the chief kept screaming ‘Shoot! Shoot!’” Andy shook his head. “Zealots. What good are they?”

“Shades of Bonnie and Clyde,” Evan said. “Were they hit?”

“They dove out of the car and ran while the Canadian guards yelled ‘Arret! Arret!’ at the American guards. The Americans shot up the car. Bullets zinged over Betty and Dalton’s heads. By all accounts, it was crazy,” Andy said.

“Did they head for the woods?” Evan asked.

“Yeah, and they’d almost made it when that police chief caught up with them,” Andy said. “He winged Betty in the shoulder.”

Evan leaned forward, his elbows resting on his knees. “I had no idea. Then what?”

“Dalton lunged at the guy. Can you imagine lunging at a nut case who’s got a loaded gun and likes using it?” Andy said. “Betty had passed out so she never got to see it but I gather Dalton made hash out of that police chief. And the Canadians just watched for a while before they stepped in. It made a big stink in the temperance newspapers down here because they literally threw him back across the border.”

“I’ll bet there was a stink,” Evan said. “That guy was gutsy.”

“Yeah, I’ll say. Betty and Dalton stayed in Canada for months after that. My grandfather drove his motorcycle up to see them a couple of times,” Andy said. “He owned an Indian. That’s the gas tank from it up there.” He pointed to a shelf nailed to the side of the stairs. “It was a fabulous bike. Somewhere around here, there’s a scrapbook of Betty’s where she pasted in articles that ran in the Montreal newspapers around that time. Seems that Dalton got to be something of a hero up there. By that time, the Canadians had had enough of America’s Prohibition because of the bootlegging over the border.”

“Yeah, I’ll say. Betty and Dalton stayed in Canada for months after that. My grandfather drove his motorcycle up to see them a couple of times,” Andy said. “He owned an Indian. That’s the gas tank from it up there.” He pointed to a shelf nailed to the side of the stairs. “It was a fabulous bike. Somewhere around here, there’s a scrapbook of Betty’s where she pasted in articles that ran in the Montreal newspapers around that time. Seems that Dalton got to be something of a hero up there. By that time, the Canadians had had enough of America’s Prohibition because of the bootlegging over the border.”

“So when did Betty come back home?” Evan asked.

“I guess she and Dalton came to an understanding because she wanted to come back to Vermont and he wanted to stay in Canada,” Andy said. “Betty’s mother was very ill, and she wanted to nurse her.”

“Did she ever make peace with her father?” Evan asked.

“I don’t know if I’d put it quite like that,” Andy said. “The old cuss was the one that bought the Cooper family cabin down in the Campgrounds. After he moved there, nobody in the family saw him much. His wife, her name was Penny, died surrounded by family. Everyone adored her.”

“I’m guessing the great-grandfather died alone,” Evan said.

“Alone and unmourned, from what I’ve heard,” Andy said. “Do you know he’s the only Cooper not buried in the family plot. No one wanted to be next to him for eternity. Anyway, the ending of the story is this. The Depression started in 1929, and everyone was hurting in Carding. This store was struggling to survive when Betty set up her applejack-making enterprise down here. She’d learned how to make it when she was in Canada. I guess she had quite the reputation because Stanley Wilson, who got elected governor in 1932, ordered a case of it to celebrate his win.”

“So everybody knew what was going on down here?” Evan asked.

“Well, you did if you knew where to look.” Andy aimed his flashlight’s beam at the ceiling. “See that?”

It took Evan a minute but he finally saw the outline of a trap door. “I’ve never noticed that before. Where does it come out upstairs?”

“You know that funny jog at the end of aisle two?” Andy said.

Evan laughed. “Where you stock the wine now?”

“Yeah. There used to be a half-wall there, like a curtain,” Andy said. “You could come into the Coop at certain times with your empty pail or growler, walk around the wall, down the steps that used to be here, and Aunt Betty would fill you up from one of these barrels.” He let a hand rest on the nearest cask.

“So that’s why they’re always here,” Evan said. “For Betty.”

Andy nodded. “She saved this store. You and I wouldn’t be here now if it wasn’t for her. I think of it as her memorial. It’s the least I can do.”

“So you think that she got upset because it was all messed around, and that’s why…?”

“No, I’m sure that what you saw was electrical,” Andy said. “You’re right about it needing to be looked at. I’ll call an electrician in the morning.”

Evan’s radio squawked and he jumped up. “Oops, gotta go,” he said. “Glad nothing serious was wrong, Andy.”

“Can you see yourself out?” Andy asked. “I still need to put wood in the furnace.”

“Sure, sure.” Evan took the stairs two at a time. “I’ll lock the door behind me.”

Andy waited until all was quiet then he made his way to the wood-burning furnace. He hummed what he remembered of the Canadian national anthem as he stacked logs on the pile of pulsating coals then shut the door. He waited until he heard the muted road of flame that let him know the fire had caught then adjusted the controls.

When he got to the shelf attached to the stairs, he reached behind the gas tank from his grandfather’s Indian motorcycle, and fished around until he found a cloth bag that held a bottle and shot glass. He carefully set the glass in the center of the largest barrel and poured a measure of golden liquid into it. He smiled as he re-corked the bottle, and checked that the chairs were in the right place.

“Sorry about that, Betty,” he said quietly. “Some new kids just started in the store and they didn’t know about leaving your stuff alone. Is everything OK now?”

Andy didn’t know what to expect. Betty had never answered him. After a moment, he sighed and reached up to flip off the lights. When his fingers got close enough to the metal face plate, a spark of static electricity arced across the space. The spark was green.

Andy chuckled. “Well, you’re welcome.”

And then he went upstairs to bed.

Sonja Hakala has been a writer and publishing professional for three decades now. She is the author of ten books (four novels about a fictional town in Vermont called Carding and six works of non-fiction) as well as the editor of an eleventh.

Sonja Hakala has been a writer and publishing professional for three decades now. She is the author of ten books (four novels about a fictional town in Vermont called Carding and six works of non-fiction) as well as the editor of an eleventh.

She's worked in newspapers and magazines and was the marketing manager for a traditional publishing company. As a publishing professional, she's edited and designed numerous books for authors around the world who wanted to independently publish their work.

She spoke at the League's Fall Conference in Shelburne about the many contemporary publishing options for today's authors.

In addition to her books about Carding, Vermont, Sonja publishes a short story about the town and its inhabitants every Thursday on her website, sonjahakala.com.